Is Java too slow for DHT11? Pi4Jv2 and pigpio

Java is certainly not the first choice for embedded, at least not for edge devices. But here I am with a cheap temperature sensor connected to a Raspberry 3B with some Java runtime.

Besides the temperature, the DHT11 also responds with relative humidity in the same way as its more precise successor DHT22. Within a total of 40 bits, you will find two times 8bit integral and decimal data for humidity and temperature, ending with an 8bit check-sum.

Currently, Pi4J stands as the most widely used library for managing "all things Java on Raspberry Pi". You can come across some examples that are supposed to retrieve the measurements from DHT11 using Java/Pi4J straight in Google. It takes a few minutes to realize that they either function as a wrapper for executing Python code or encounter difficulties in timely reading the transmission.

Why is that? Is Java just too slow?

The predominant characteristic of Java is that it compiles to bytecode which is an intermediate representation that can be run on different systems. Because of this, its performance is relatively slower than the native implementation. The situation changes once the JIT compiler identifies performance-critical areas and optimizes them by compiling them into highly efficient native code. Now and then, some garbage collection will also stop or slow down your program for a teeny bit of a second.

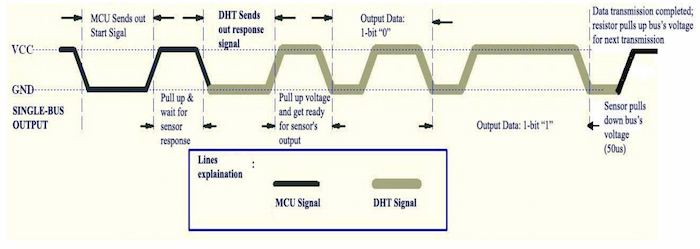

The transmission is single-wire two-way and is said to last around 18 + 4 ms:

But what timings are required? Let's see:

- MCU (RPI) sends a start signal by pulling down voltage for at least 18 ms;

- MCU pulls up voltage and waits for DHT response for 20-40 µs;

- DHT pulls down the voltage for 80 µs;

- DHT pulls up the voltage for 80 µs;

- DHT sends 40 bits of data:

- DHT pulls down the voltage for 50 µs;

- DHT pulls up the voltage for either:

- 26-28 µs denoting '0' or;

- 70 µs indicating '1' bit;

- DHT ends the data transmission by pulling down the voltage;

- DHT ends the communication by pulling up the voltage.

Two crucial polling constraints result from these timings. We must be able to switch the GPIO fast enough from output to input (180 µs) and sample at a fast enough rate to distinguish the duration of the signal. What is fast enough, you might ask?

The answer was already by Nyquist and Shannon, and it's fs ≥ 2 × fmax, where:

- fs is the sampling rate (in samples per second or Hz);

- fmax is the highest frequency component in the signal (in Hz).

fs ≥ 80 kHz = sample every 12.5 µs

Let's run some JMH benchmarks to see if it's achievable.

Java Microbenchmark Harness for Pi4J v2

Pi4J had a second major release recently, and the first version was since discontinued. A simple maven setup enables seamless building, and as for the development environment, I use a PC with a remote (SSH) RPI run target. One caveat is that the Pi4J 2.3.0 uses a C library pigpio that requires root access to the GPIO.

Note: You can enable root login on the RPI, but then you lose the option to sigterm the process when using underlying OpenSSH. In the worst case, you can try killing it from a different session.

Here is the essential Maven project config:

<properties>

<pi4j.version>2.3.0</pi4j.version>

<jmh.version>1.36</jmh.version>

</properties>

<dependencies>

<dependency>

<groupId>com.pi4j</groupId>

<artifactId>pi4j-core</artifactId>

<version>${pi4j.version}</version>

</dependency>

<dependency>

<groupId>com.pi4j</groupId>

<artifactId>pi4j-plugin-raspberrypi</artifactId>

<version>${pi4j.version}</version>

</dependency>

<dependency>

<groupId>com.pi4j</groupId>

<artifactId>pi4j-plugin-pigpio</artifactId>

<version>${pi4j.version}</version>

</dependency>

<dependency>

<groupId>org.openjdk.jmh</groupId>

<artifactId>jmh-core</artifactId>

<version>${jmh.version}</version>

<scope>test</scope>

</dependency>

<dependency>

<groupId>org.openjdk.jmh</groupId>

<artifactId>jmh-generator-annprocess</artifactId>

<version>${jmh.version}</version>

<scope>test</scope>

</dependency>

</dependencies>

Followed by the initialization and read benchmarks.

@State(Scope.Benchmark)

@Fork(value = 1)

@Warmup(iterations = 0)

@BenchmarkMode(Mode.SingleShotTime)

@OutputTimeUnit(TimeUnit.NANOSECONDS)

@Threads(value = 1)

public class Pi4Jv2Benchmark extends JMHJITGPIOBenchmark {

Context pi4j;

DigitalInput input;

@Setup(Level.Trial)

public void setUp() {

pi4j = Pi4J.newAutoContext();

DigitalInputConfig inCfg = DigitalInput.newConfigBuilder(pi4j)

.address(DHT11_GPIO)

.pull(PullResistance.OFF)

.debounce(0L)

.provider("pigpio-digital-input")

.build();

input = pi4j.create(inCfg);

}

@TearDown(Level.Trial)

public void tearDown() {

pi4j.shutdown();

}

@Benchmark

@Measurement(iterations = 1000)

public void testRead_100(Blackhole blackhole) {

blackhole.consume(input.state());

}

@Benchmark

@Measurement(iterations = 10)

public void testInitialize_10() {

input.initialize(pi4j);

}

//...

}

In these benchmarks, I'm trying to get the idea of how much the duration will decrease after the nth execution of the method (SingleShotTime mode). Hopefully, JIT decides to compile some stuff into superfast native code.

Benchmark Mode Cnt Score Error Units

Pi4Jv2Benchmark.testInitialize_1 ss 137497.000 ns/op

Pi4Jv2Benchmark.testInitialize_10 ss 10 167089.200 ± 49132.217 ns/op

Pi4Jv2Benchmark.testInitialize_100 ss 100 174594.980 ± 20509.078 ns/op

Pi4Jv2Benchmark.testInitialize_1000 ss 1000 144984.940 ± 6403.755 ns/op

Pi4Jv2Benchmark.testInitialize_10000 ss 10000 123345.067 ± 5324.980 ns/op

Pi4Jv2Benchmark.testRead_100 ss 100 92882.500 ± 7699.051 ns/op

Pi4Jv2Benchmark.testRead_1000 ss 1000 104655.871 ± 29442.669 ns/op

Pi4Jv2Benchmark.testRead_10000 ss 10000 53066.052 ± 1810.808 ns/op

Pi4Jv2Benchmark.testRead_100000 ss 100000 7755.533 ± 308.039 ns/op

To achieve less than the 12.5 µs read duration time, it took the JIT compiler somewhere less than 100000 iterations. You would have to run a different benchmark mode to estimate minimal time for stable reading warm-up, but my estimated guess would be within 10s.

Can ahead-of-time (AOT) compilation help?

Recent years gave us the opportunity of building a native image using GraalVM.

All you need is to download the VM and use the native-image tool.

Maven org.graalvm.buildtools:native-maven-plugin streamlines this process. Two files in the META-INF/native-image are additionally required for this process.

The proxy-config.json specifies dynamic proxy interfaces used by Pi4J and jni-config.json helps the compiler with linking native pigpio callback to the Java.

<profile>

<id>native</id>

<build>

<plugins>

<plugin>

<groupId>org.graalvm.buildtools</groupId>

<artifactId>native-maven-plugin</artifactId>

<version>0.9.22</version>

<extensions>true</extensions>

<executions>

<execution>

<id>build-native</id>

<goals>

<goal>compile-no-fork</goal>

</goals>

<phase>package</phase>

</execution>

</executions>

<configuration>

<skipNativeTests>true</skipNativeTests>

<verbose>true</verbose>

<mainClass>dev.termian.rpidemo.test.CrudeNativeTestMain</mainClass>

</configuration>

</plugin>

</plugins>

</build>

</profile>

Inevitably, the mvn clean package -Pnative takes a considerable amount of memory (~2-3G), time (~3 min) and the target architecture host.

Limited RAM resources on RPI can be circumvented by increasing swap, but it is not really intended for such workloads that the build duration reaches 15 minutes.

An alternative is to use a virtual server. For example, Oracle Cloud Infrastructure provides an aarch64 box with a comfortable amount of free resources.

### OCI

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

3.2s (1.6% of total time) in 24 GCs | Peak RSS: 2.22GB | CPU load: 0.96

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

Finished generating 'rpidemo' in 3m 24s.

### RPI 3B

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

108.4s (12.0% of total time) in 102 GCs | Peak RSS: 0.77GB | CPU load: 2.81

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

Finished generating 'rpidemo' in 14m 55s.

Now skipping to my unscientific test, the results are remarkably satisfactory, excluding occasional overhead of the garbage collection. For sure, the initialization time seems much better than with the JIT. Maybe some parts were not hot enough to trigger the compiler?

Pi4Jv2 Initialization duration: 11927ns

Pi4Jv2 Read duration: 7083ns, state HIGH

At this point I stopped due to the cumbersomeness of the process, but there is more. According to the Oracle's GraalVM Edition feature and benefit comparison, the CE edition that I've used "is approximately 50% slower than JIT compilation". However, GraalVM Enterprise Edition compiled native executables can be faster than the JIT using Profile-Guided Optimizations. I'm mentioning this because the EE may be used free of charge on OCI. The caveat would be how to properly profile-guide it, given the dependency on the pgpio lib.

The native executable on RPI doesn't handle well the lookup of libpi4j-pigpio.so binding library, you will have to unpack it from

pi4j-library-pigpio-2.3.0.jar!lib/aarch64/and provide its location using Java system propertypi4j.library.path. On the other hand, for OCI PGO, you will also be missing the native pigpio libs that are usually preinstalled on RPI.

Speeding up with pi4j-library-pigpio

Surprisingly, you can skip one layer of Pi4J by directly using the pi4j-library-pigpio included by the pi4j-plugin-pigpio.

It has much less abstraction (lower-leveled, fewer object creations less validation) and maintains a tight binding to the pigpio.

@State(Scope.Benchmark)

@Fork(value = 1)

@Warmup(iterations = 0)

@BenchmarkMode(Mode.SingleShotTime)

@OutputTimeUnit(TimeUnit.NANOSECONDS)

@Threads(value = 1)

public class PIGPIOBenchmark extends JMHJITGPIOBenchmark {

@Setup(Level.Trial)

public void setUp() {

PIGPIO.gpioInitialise();

PIGPIO.gpioSetMode(DHT11_GPIO, PiGpioConst.PI_INPUT);

PIGPIO.gpioSetPullUpDown(DHT11_GPIO, PiGpioConst.PI_PUD_OFF);

PIGPIO.gpioGlitchFilter(DHT11_GPIO, 0);

PIGPIO.gpioNoiseFilter(DHT11_GPIO, 0, 0);

}

@TearDown(Level.Trial)

public void tearDown() {

PIGPIO.gpioTerminate();

}

@Benchmark

@Measurement(iterations = 1000)

public void testRead_100(Blackhole blackhole) {

blackhole.consume(PIGPIO.gpioRead(DHT11_GPIO));

}

@Benchmark

@Measurement(iterations = 10)

public void testInitialize_1() {

PIGPIO.gpioSetMode(DHT11_GPIO, PiGpioConst.PI_INPUT);

}

//...

}

JMH:

Benchmark Mode Cnt Score Error Units

PIGPIOBenchmark.testInitialize_1 ss 24479.000 ns/op

PIGPIOBenchmark.testInitialize_10 ss 10 12317.300 ± 6646.228 ns/op

PIGPIOBenchmark.testInitialize_100 ss 100 13350.620 ± 3460.271 ns/op

PIGPIOBenchmark.testInitialize_1000 ss 1000 12948.114 ± 2407.712 ns/op

PIGPIOBenchmark.testRead_100 ss 100 24913.410 ± 21993.740 ns/op

PIGPIOBenchmark.testRead_1000 ss 1000 18125.702 ± 1854.193 ns/op

PIGPIOBenchmark.testRead_10000 ss 10000 8577.220 ± 1288.801 ns/op

PIGPIOBenchmark.testRead_100000 ss 100000 1837.087 ± 83.765 ns/op

Now this looks much better. You can anticipate stable communication starting from the first signal.

Blazing precise pigpio

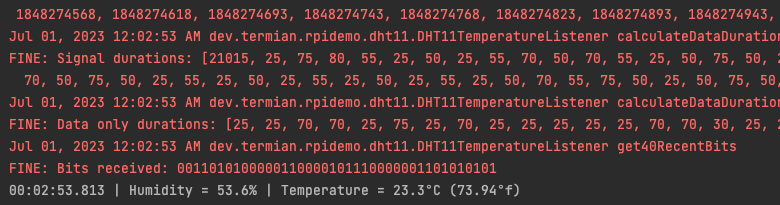

As a Java developer, polling to get the precise duration of the signal didn't sit well with me. Midway, I started looking for an interface that already implements this information.

I looked up the documentation for pigpio and found some promising functions like state alert listening. In the Pi4J, this function was hidden by a default 10 µs debounce configuration combined with missing tick (state switch time) information. That is why it wasn't timely reporting state changes. One level lower in the pi4j-library-pigpio, you will find the expected interface, as well as you will be able to change the default 5 µs pigpio sampling rate.

Taking a further look into the pigpio header definitions, it seems there are two threads. One is for registering the state change, and the other one is for reporting to the callback. This makes the reading blazing precise (even to 1 µs), as well as providing the callback enough time for processing (within a quite lenient buffer/time). Traded for possible delays in the reporting. Perfect for my case.

public class DHT11TemperatureListener implements PiGpioAlertCallback {

//...

private final long[] signalTimes = new long[MCU_START_BITS + DHT_START_BITS + DHT_RESPONSE_BITS];

private final int gpio;

private int signalIndex;

public DHT11TemperatureListener(int gpio, int sampleRate) {

this.gpio = gpio;

Arrays.fill(signalTimes, -1);

initPGPIO(gpio, sampleRate);

}

protected void initPGPIO(int gpio, int sampleRate) {

PIGPIO.gpioCfgClock(sampleRate, 1, 0);

PIGPIO.gpioSetPullUpDown(gpio, PiGpioConst.PI_PUD_OFF);

PIGPIO.gpioGlitchFilter(gpio, 0);

PIGPIO.gpioNoiseFilter(gpio, 0, 0);

}

public HumidityTemperature read() throws InterruptedException {

sendStartSignal(); // #1

waitForResponse();

try {

return parseTransmission(signalTimes); // #4

} finally {

clearState();

}

}

private void sendStartSignal() throws InterruptedException {

PIGPIO.gpioSetAlertFunc(gpio, this);

PIGPIO.gpioSetMode(gpio, PiGpioConst.PI_OUTPUT);

PIGPIO.gpioWrite(gpio, PiGpioConst.PI_LOW);

TimeUnit.MILLISECONDS.sleep(20);

PIGPIO.gpioWrite(gpio, PiGpioConst.PI_HIGH);

}

private void waitForResponse() throws InterruptedException {

PIGPIO.gpioSetMode(gpio, PiGpioConst.PI_INPUT);

synchronized (this) {

wait(1000); // #3

}

}

@Override

public void call(int pin, int state, long tick) {

signalTimes[signalIndex++] = tick; // #2

if (signalIndex == signalTimes.length) {

logger.debug("Last signal state: {}", state);

synchronized (this) {

notify(); // #3

}

}

}

//...

}

This approach allows for the implementation of a more readable, higher-level code similar to what you would typically expect in Java. All you need to do is to save the timings (#2) of the signal after the initial registration (#1). On receiving the last bit of the transmission, the callback thread wakes up your calling thread (#3). After that, you can take your time to parse the signal times into data bits and then to the relative humidity and temperature (#4).

You will find the full demo code at https://github.com/t3rmian/rpidemo. If you want to try out a polling solution, take a look at the "Unable to read DHT22 sensor" discussion on pi4j-v2 project.

Summary

Sometimes Java can be slow, but it still has its charms. You can take advantage of JIT or build native image with GraalVM SE or EE with some sprinkle of PGO. With Pi4J when pushed for time, you can skip the high-abstraction packages and use the provided pi4j-library-pigpio. The best results are often achieved with thoughtfully crafted interfaces like pigpio threaded alert callbacks. As long as you don't need a hard-real time system implementation…